How does mandatory and voluntary carbon trading work?

Niamh Dennehy-Maher of Allen & Overy and Robert Lang-Anderson of Bank of America examine each market, explain how carbon trading schemes are set up and what the allowances and credits issued under mandatory and voluntary programmes represent.

Mandatory carbon markets, also known as compliance carbon markets, exist as a result of individual national or supranational commitments under global climate agreements such as the 1997 Kyoto Protocol or the 2015 Paris Agreement. They are created by statute or similar formal mechanism and operate under a legal framework. They often function as ‘cap and trade’ schemes known as emissions trading systems (ETSs). There are many examples of mandatory carbon markets, including:

- the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS), the world’s first international emissions trading system and still the biggest. It was established in 2005 following the Kyoto Protocol which set, for the first time, legally binding emissions reduction targets for 37 industrialised countries and the European Union;

- the UK Emissions Trading Scheme (UK ETS), which was established in January 2021 to replace the EU ETS in the UK following Brexit. The UK ETS closely models the structure of the EU ETS; and

- mandatory schemes across the world including in China, Japan, Mexico, South Africa, South Korea and (at a state level) the US. As of today, there are about 29 mandatory emissions trading schemes in force worldwide.

In this article, we will focus on the UK ETS as an example of how a compliance carbon market works, who can participate in that market and what it is intended to achieve.

UK ETS

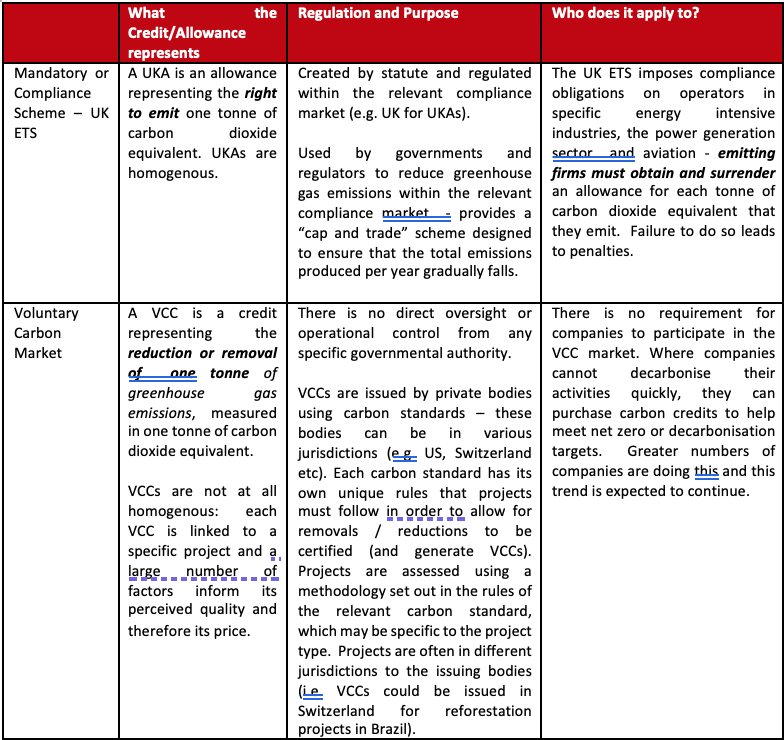

Mandatory carbon markets are a key tool used by governments and regulators to combat global warming and reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The UK ETS is an example of a ‘cap and trade’ scheme that imposes compliance obligations on operators in specific energy intensive industries, the power generation sector and aviation, placing a cap on the total amount of greenhouse gas emissions that can be emitted by those sectors in a given year. The cap is reduced each year, thus ensuring that the total emissions produced gradually fall. Emitting firms must obtain and surrender an allowance for each tonne of carbon dioxide equivalent that they emit. A UK Emissions Trading Scheme Allowance (a UKA) represents the right (allowance) to emit one tonne of carbon dioxide equivalent. A certain number of UKAs are allocated to participants in the sector each calendar year for free and they can buy further UKAs either at auction or on the secondary market, and/or trade them in the derivatives market.

At the end of a year, when a participant has to report its greenhouse gas emissions, it must retire sufficient UKAs for each tonne emitted. If it fails to do this, the firm will face fines and other penalties and, if the opposite is the case, and the firm succeeds in reducing its greenhouse gas emissions to a level to below what it is permitted, it can either retain spare allowances to cover its future needs or else sell them to other entities that are short on allowances.

Market participants

As noted above, the UK ETS applies to energy intensive industries, the power generation sector and aviation sector. An entity which is not subject to UK ETS compliance obligations (such as an investment firm or credit institution) can hold and trade UKAs as an activity in and of itself. Companies and other market participants may wish to buy or sell UKAs for a variety of reasons, including to meet compliance needs, take positions on expected price movements or provide liquidity.

The registry

A specifically designed trading registry (the UK ETS Registry) has been developed for the UK ETS and UKAs are held in accounts at that registry, which operates in a similar way to an online bank account for UKAs, recording issuances, transfers and surrenders. There are certain accounts, known as Operator Holding Accounts and Aircraft Operator Holding Accounts, used only by installation operators or aircraft operators. An entity which is not subject to UK ETS compliance obligations can open a Trading Account for the purpose of holding and trading UKAs.

Voluntary carbon markets

Voluntary carbon markets exist outside of (and alongside) mandatory carbon markets and enable companies and individuals to purchase carbon credits on a voluntary basis as a way to offset greenhouse gas emissions and otherwise meet their sustainability goals. Generally speaking, voluntary carbon markets are voluntary insofar as nobody has to participate in them; they are private initiatives managed predominantly by non-profit organisations and are not directly operated by government.

What are voluntary carbon credits?

A voluntary carbon credit (VCC) is a token representing the avoidance or removal by a certified climate mitigation project of greenhouse gas emissions, typically measured as a tonne of carbon dioxide equivalent. A VCC allows an entity to ‘offset’ emissions by purchasing VCCs generated by climate mitigation projects which remove or reduce greenhouse gas emissions. This is commonly known as ‘offsetting’ emissions, with the terms ‘offsets’ and ‘carbon credits’ often used interchangeably. Projects that improve energy efficiency measures in industrial plants or that protect forests from being cut down may qualify as climate mitigation projects capable of generating VCCs, as these each reduce the flow of emissions into the atmosphere. Other projects, such as new technology for carbon air capture or reforestation or planting trees on new land, may also qualify as they remove carbon from the atmosphere.

VCCs are issued in respect of climate mitigation projects by bodies (usually NGOs) using carbon standards (examples of which are The Verified Carbon Standard and The Gold Standard), which certify that a particular climate mitigation project meets its stated objectives and its stated volume of emissions. VCCs can be obtained in the primary market, or bought / sold / traded in the secondary and derivatives markets. Each carbon standard has its own unique rules that all projects must follow in order to be certified. For a project to generate VCCs under any carbon standard, it must typically demonstrate the greenhouse gas reductions or removals are real, measurable, permanent, additional, independently verified, unique and traceable. Projects are assessed using a methodology set out in the rules of the relevant carbon standard, which may be specific to the project type.

The fact that there are multiple voluntary programmes and that they do not share standardised rules has made it challenging for purchasers of VCCs to assess the integrity and quality of the credits. In March 2023, the Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market, an independent governance body for the voluntary carbon market, published the 10 Core Carbon Principles (CCPs). These standards aim to provide a readily identifiable, market-wide benchmark for carbon credit quality and integrity. Adoption of the Core Carbon Principles across the voluntary market would help promote growth of the voluntary carbon markets through improved transparency, liquidity and bankability.

Market participants

There has been a wave of public and private commitments by countries and companies globally to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to net zero, beyond any regulatory requirement to do so. A number of high profile corporates have used voluntary carbon credits to offset their emissions, including Google’s parent company, Alphabet, which in 2020 announced that it had managed to eliminate its entire lifetime carbon footprint by purchasing high quality voluntary carbon credits.

The voluntary carbon market is projected to see significant growth in the coming years:

- according to a 2021 McKinsey report, demand for voluntary carbon markets is projected to increase by a factor of 15 or more by 2030;

- the Taskforce on Scaling Voluntary Carbon Markets projects that the value of the voluntary carbon markets could reach $5 billion–50 billion by 2030; and

- Bloomberg predicts that VCC prices could increase by up to 50 fold by 2050 due to the expanding universe of sustainability goals and a surge in demand from carbon emitters with no alternatives to offsets.

When an entity holds a VCC, it owns the right to claim responsibility for the reduction or removal of emissions. To use the VCC to offset its emissions, the holder must ‘retire’ it, meaning that it can no longer be sold or transferred.

VCC registries and credits

Once a project is certified pursuant to a carbon standard, it generates a specified number of VCCs, each of which is given a unique serial number and issued by the relevant carbon standard’s administrator into its registry, where it can be held, delivered, retired or cancelled. VCCs are recorded by different registries/registry administrators and are subject to the contractual framework of the relevant registry and its terms of use or registry rules. VCCs often have varied nomenclature between the standards which can sometimes lead to confusion. For example, The Gold Standard refers to them as ‘carbon credits’, whereas The Verified Carbon Standard refers to them as ‘Verified Carbon Units’.

Conclusion - similar but different

Unlike the mandatory carbon markets, voluntary carbon markets are typically not directly managed by any specific governmental authority. Also, unlike UKAs, VCCs are not at all homogenous: each VCC is linked to a specific project and a large number of factors inform its perceived quality and therefore its price. For example, a VCC generated by a project that removes greenhouse gas from the atmosphere (e.g. reforestation) may trade at a higher price than one generated by a reduction project (e.g. funding the transition to renewable energy). There have been limited circumstances (in California, Mexico and Japan) where VCCs have been recognised by governments and permitted to interact with compliance markets, however, such interaction is rare and on the whole the voluntary and compliance carbon markets remain distinct from one another and exist in parallel (see table below for a summary of the differences).

Although outside the scope of this article, credits issued under international mechanisms, such as Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, are expected to become increasingly important going forward and it will remain to be seen how this “third” category of credits, once operational, might interact with the mandatory and voluntary carbon markets otherwise discussed above.

Activities in scope of the UK ETS are listed in Schedule 1 (aviation) and Schedule 2 (installations) of the Greenhouse Gas Emissions Trading Scheme Order 2020.

Tom d’Ardenne, who holds a counsel role in Allen & Overy’s Global International Trade and Regulatory Law Group, also contributed to this article.