African infrastructure: Taking the local funding route

Financing the $170 billion African infrastructure gap using domestic capital pools isn’t quite a pie in the sky – there are several financing tools that are already sourcing local investment. But limited savings rates and poor investor appetite are likely to keep any capital dent small for now.

Channelling the growing pool of African capital – via local and regional funds, banks, ECAs and DFIs – into African infrastructure at scale has every logical argument going for it. From mitigating forex risks to deepening capital markets, growing the local pool of funding will provide a multitude of benefits. Furthermore, poor infrastructure reportedly adds 30-40% to the costs of goods traded among African countries, as well as a plethora of other hardships.

But the logic ignores some of the realities of the potential African funding base. According to Samuel Chasia, director of business development – capital markets at GuarantCo (part of the PIDG Group), this prospect faces two big issues: “What is truly a hindrance to getting financing into infrastructure projects is capacity and, in a lot of financial institutions, appetite. The combination of these two things is detrimental”.

A significant obstacle is savings (or the lack of). In comparison to other emerging economies with similar populations and GDPs, savings rates are very low across Africa – according to the Africa Financial Industry Summit, only 15% of Africans have pension coverage, far below the international average of 54%. Extending coverage to the 80% of the workforce in the informal sector poses a further mammoth task.

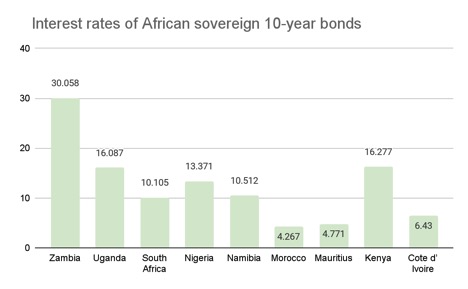

The second issue is the high cost of government borrowing: of the nine African sovereigns currently issuing ten-year bonds, the benchmarks range between 426bp and 3005bp (depicted in the graph below). As Ope Onibokun, investment director for infrastructure & climate at BII, says “If you can earn 20% borrowing from the government, which is considered risk-free, investing in infrastructure could be relatively unattractive if the expected returns don’t stake up”.

Source: Investing.com

Source: Investing.com

Elena Palei, global head of infrastructure at MIGA, soundly encapsulates the reality, “large-scale African infrastructure projects could not rely 100% on domestic liquidity.” Small ticket locally funded deals can help to close the infrastructure gap – but only if a plethora of such deals are realised.

Institutional investment routes

In March 2022, IFC signed a $10 million partnership with Senegal’s sovereign wealth fund (SWF), Le Fonds Souverain d’Investissements Strategiques (FONSIS), to develop 200 homes in Dakar over the next eight to ten years. The small-ticket deal can help scale up impact and will mobilise additional local and international institutional investment.

SWF sizes could increase with hikes in commodity prices – but this might not be as likely as hoped. Nigeria Sovereign Investment Authority (NSIA) receives excess cash from crude oil with barrel prices increasing to $18 each in the past 12 months – but pipeline closure and constrained production has led the country’s oil output to new lows. Conversely, continuing political unrest and underinvestment will continue to limit SWF inflows, which already struggle to make an impactful capital dent: the continent’s SWFs only saw incomes of $130 billion over the last five years (2016-2020).

In Kenya, Nigeria, and South Africa, pension and insurance represents a slightly more significant pool of liquidity, with AUMs of $12.2 billion, $30.2 billion, and $302.1 billion, respectively (2021). Similarly to SWFs, these sources match the character requirements of infrastructure investment: they have a long-term view and will benefit from infrastructure cash flows which allow them to meet obligations like premium pay-outs. In short, educating institutional investors about funding infrastructure is key to ensuring their move away from government treasuries.

However, risk is not just as a matter of returns, as Onibokun highlights: “it is essential to meet the cash expectations of policy holders – you can’t expect pensioners to come to the end of their policy and find out there’s no money”. Any capacity gaps in infrastructure expertise need to be addressed thoroughly before encouraging investment – TA, consultancy advice, and guarantee structures could soften this risk.

Both pools lack the liquidity and capacity necessary for scaled up infrastructure investment – but blending these sources together, as Africa50 has successfully managed to do with the Africa50 Infrastructure Acceleration Fund, in a way resolves both limitations.

The $500 million fund was signed in July 2023 and secured subscription agreements from NSIA, IFC, AfDB the Arab Bank for Economic Development in Africa (BADEA), BOAD, CDC Senegal, CDC Benin, CNSS Togo, CDG Invest, and Attijariwafa Bank of Morocco, as well as pension funds, asset managers, retirement agencies and two international institutional investors. It marks the first private vehicle infrastructure platform launched by the firm and an “unprecedented milestone for Africa”, according to AfDB, which invested $20 million of equity into the fund.

It is still unclear whether the fund will harness one of the greatest assets of domestic mobilisation: local currency financing. Aside from the construction of the Malicounda power station in Senegal which cost Africa50 and Oragroup XOF50 billion ($90 million) in March 2021, the firm has tended to favour dollars and euros. Not doing so risks cutting further into the already limited domestic savings pools with forex risk adjustments.

“The most efficient way to finance these infrastructure projects is with local currency otherwise you’re introducing currency mismatches which is a cost that ultimately somebody has to bear” says Chasia, “If you’re financing something for 15-20 years, any mismatches will ultimately impact the affordability and sustainability of the project.”

Local currency routes

DFI guarantees can finance local currency projects with domestic involvement and GuarantCo has a proven track record: The DFI provided a XAF23.5 billion ($38.4 million) guarantee solution to Societe Generale Cameroun and Societe Commerciale de Banque Cameroun (SCB) to finance the modernisation of 14 toll plazas across Cameroon in June 2022. The financing comprises a 14-year combined liquidity extension and partial credit guarantee to support the debt and lend comfort to the two banks combined loan of XAF32.2 billion ($52.5 million). Six months later, GuarantCo and African Guarantee Fund (AGF) provided GreenYellow with a nine-year credit guarantee of MGA 23.5 billion ($5.4 million) to a syndicate of local banks, led by Societe Generale, to finance a 20MW solar plant extension alongside a 5MW solar battery storage system in Madagascar.

Both projects managed to unlock locally sourced, local currency financing on suitable tenors to project financing. The bones of sustainable structuration are there – but guarantees are still hesitant to take on larger tickets or construction risk.

Public debt markets pose another option for local currency financing and twenty green bonds have been floated in Africa since 2020, raising a total of $2.78 billion. As highlighted above, bonds are attractive to investors for their ability to deliver reliable, high returns – channelling that income into infrastructure seems a simple solution.

In October 2019, GuarantCo provided a 50% partial credit guarantee to investors in Acorn Holding’s KES 4.3 billion ($43 million equivalent) note programme, covering principal and interest due to fund the construction of accommodation for 5,000 students in Nairobi. The bond was priced at 12.25% and was rated B1 by Moody’s (higher than the sovereign bond rating).

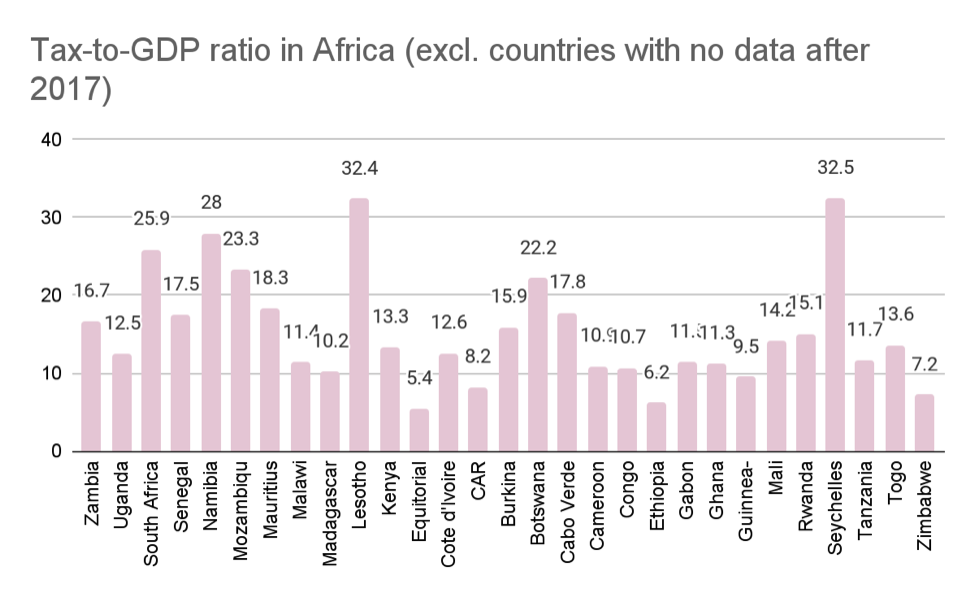

Beyond GuarantCo’s innovative deal, however, the continent’s public debt markets are invariably thinly traded and dominated by government issues, which raises an issue for keeping a lid on sovereign debt. African countries have an average 70% debt-to-GDP ratio which is below the global mean but not the worst – but the greater issue arises when you come to tax-to-GDP ratios. As visible in the graph below, for some sovereigns already facing debt sustainability issues (like Ghana, Zambia, Ethiopia, Gabon) scaling up bonds could make debt unserviceable.

Source: World Bank

On the corporate side, project finance requires large sums to be drawn down at the start for construction, the riskiest phase of the venture. Private investors may be interested in cash flows from maturer infrastructure but these bonds are almost entirely absent from the continent.

The first listing of an investment-grade rated infrastructure project bond took place in April 2013 in South Africa, with institutional investors entirely backing the 44MW Touwsrivier Solar Project with a fixed coupon of 11% over a 15-year maturity date. Despite the innovation of the issuance, which was based on an amortising profile in place of a bullet structure effectively giving the bond a modified duration of seven years, the South African market hasn’t seen many subsequent project bonds – and they have been missing entirely from other African markets.

DFI-ECA cooperation routes

As outlined already, DFIs are a significant player on the African infrastructure landscape: according to Uxolo data, between 2021-2023 DFIs have invested $11.46 billion in this space (including closed and approved deals). Blended finance first-loss buffers are a common strategy for DFIs to protect pure play private capital investors, including local ones.

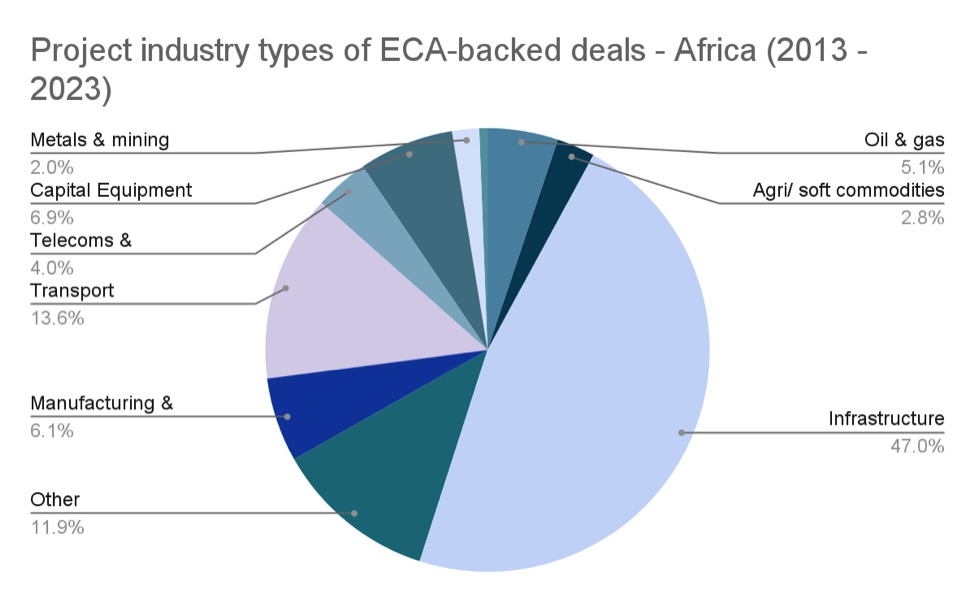

But DFIs are not the only agency financiers present on the continent: ECAs have been actively mobilising billions in international and local (mainly South African) commercial capital into infrastructure which, in the last decade, has made up 47% of African deals (according to TXF data, chart below). Overall, ECA project volumes have eclipsed DFI’s: of the 68 ECA-backed infrastructure deals which have closed between 2021-2023 have amounted to $15.3 billion (TXF data).

Source: TXF data

DFI-ECA collaborations now need to step up for the sake of increasing impact dollars: the ECA mandate reduces development to a byproduct of transactions, not the goal, and DFIs cannot achieve the SDGs solely on their own, limited, capital.

The DFIs that have been willing to collaborate on ECA-backed deals have been African; namely, AFC, AfDB, and Afreximbank. Western DFIs have been barked off by tensions around preferred creditor status, like IFC on the $2.7 billion Nacala Logistic Corridor in Southeast Africa.

With recent updates in the OECD Arrangement on Officially Supported Export Credits being touted as a “great milestone” for increasing the climate and impact objectives of ECA finance flows – by (i) increasing tenors to up to 22 years for climate-focused projects (from 18 previously); (ii) introducing further repayment flexibility, and (iii) adjusting the minimum premium rates for credit risk for longer repayment terms and obligors with higher credit risk ratings – the time has never been so ripe for DFI-ECA climate-aligned collaboration in tougher risk-climates. Underserved African infrastructure presents the perfect challenge and opportunity.

The TXF perspective

Bonds, blended finance, funds, SWFs, pensions, ECAs – combining local currency, capacity and capital is proving a difficult task across the board. The only financing source that is managing to deliver all three reliably and repeatedly is guarantees, but examples are still thin on the ground.

Guarantees can improve the bankability of specific projects, but Palei says they still aren’t “the ultimate solution” and cannot substitute sector reforms – if the tariff system is inadequate, government owned utilities are weak, government institutions involved in the regulation and supervision of projects are inadequate, then these will all deter the development of a bankable project pipeline.

Local currency is a preferable solution, but there are still cases where it isn’t possible. MIGA can only provide guarantees in convertible currencies and GuarantCo has to make allowances for hard currency when necessary to do so, such as in fragile economies. But, this inhibition might be less critical than suggested, as Chasia states that: “As an African myself, I prefer more capital in the region – there’s a need for all types of financing and, ultimately, having no essential infrastructure is a lot more expensive than having hard currency debt”.

With Chasia’s words in mind, more DFI-ECA collaboration becomes the glaringly obvious option for scaling up infrastructure capital.