Alternative financing for mining: feast or famine?

The mining industry is suffering after a decade of underinvestment. Macroeconomic pressures have further reduced a pool of money that was already limited. These issues seem to fly in the face of the received wisdom on the world’s urgent demand for metal, so what options are available to prospective miners fundraising today?

In the world of M&A, the mining industry is set for a feast. That’s the mantra for Glencore CEO Gary Nagle as he leads his firm’s efforts to woo shareholders of Teck Resources ahead of a proposed merger. So far, the Canadian miner has held firm despite Glencore’s efforts to sweeten the deal with cash incentives for those investors looking to avoid exposure to its sizeable thermal coal business. The pressure ratcheted up a notch when Teck shareholders rejected the board’s own plan to separate its copper and coal businesses, and now Canadian investors and government officials have now called for Teck to remain a fully Canadian business. Teck has been left in limbo, and observers will wait expectantly for all sides to return with reconsidered proposals soon.

Mergers and acquisitions are nothing new in mining, and Glencore’s bid for Teck is not even the biggest deal this week. Newcrest Mining has announced that it will accept a takeover bid from Newmont in a move that will create the world’s largest gold miner by some distance. Consolidation is on the rise once again as the mining majors sense another metals boom, fuelled by demand for battery-grade minerals. The only problem is that investment in new mines has continued to stagnate as junior players are left to carry the burden of exploration. Both opportunities and risks will likely abound over the coming years as states look to boost their investment in critical minerals, but for now investment in new upstream projects is still reliant on a prohibitively complex mix of project financing and alternative funds. If projected demand is to be met, more must be done to support new sources of supply.

The energy transition demands metal, and metal demands mining. This much has been well-documented in recent years as the developed world turns towards battery technology. In theory, the economic benefits of investing in new mineral deposits should be clear, especially given the recent developments in critical mineral policies in the US and the EU. However, the realities of opening a mine are rarely so clear cut. It is always important to remember that the mining industry is really a collection of very different sectors, each of which are driven by very different economic drivers. Consequently, the financing prospects of a new mine can vary wildly depending on the nature of the product and the location of the site. For a prospective miner, particularly one that cannot fund projects on its own balance sheet, it is essential that they understand the different funding options available to them.

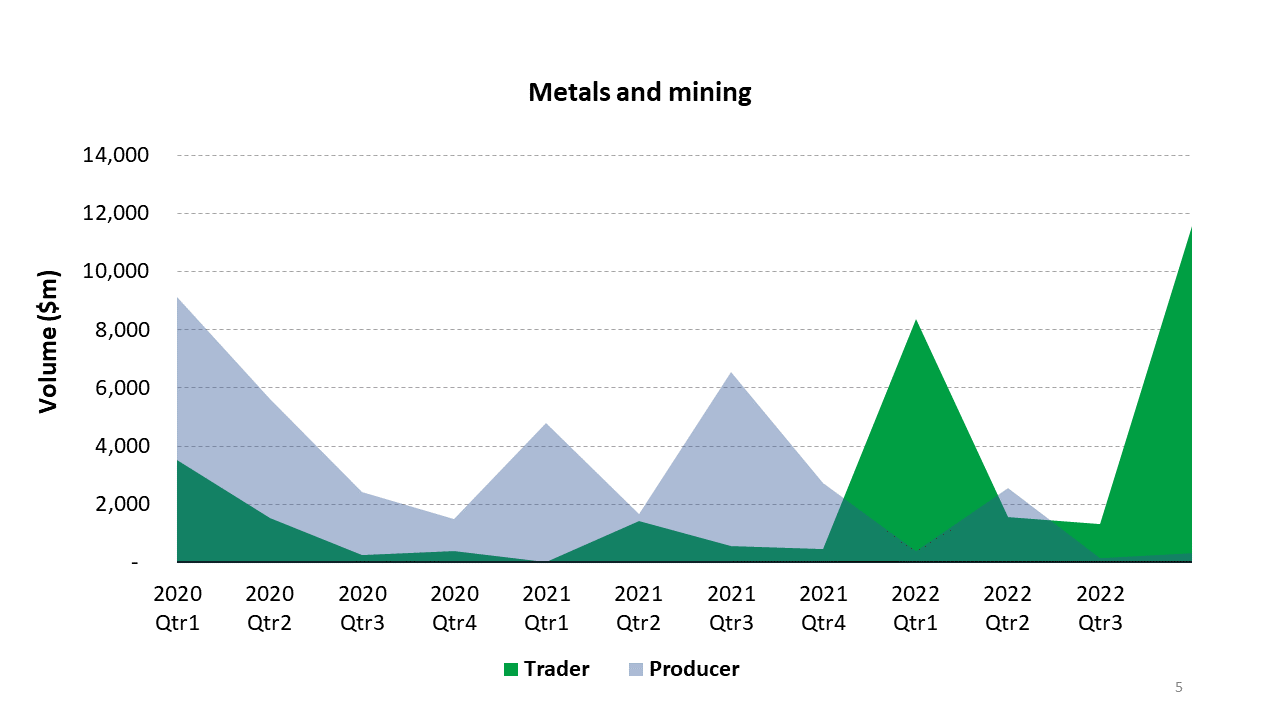

If ever there was a moment for such a re-evaluation, now would be appropriate. TXF Intelligence’s annual commodity finance data report recorded rapid growth for the metals and mining industry in 2022 after a COVID-induced hangover in 2020 and 2021. Total volumes rose to $26.3 billion, making up 17.5% of total commodity finance volumes, up from $17.7 billion the previous year. It is not always wise to buy into rhetoric in the commodities trade, but fresh demand would suggest that those sluggish volumes have room to grow.

When we break down the data, this becomes even more apparent. In 2022, loans to traders in the metals and mining industry grew rapidly to $22.8 billion. It accounted for the vast majority of the overall growth in commodity finance loans to traders. By contrast, loans to producers reached only $3.4 billion, or 7.8% of overall producer volumes. Metals and mining actually fell from the second most active producer industry to fourth. Never has the gap between expected demand and financing seemed so large.

The M&A market is hotting up, but someone must carry the burden of investing in new deposits to ensure security of supply. After all, the cost of acquisitions will only increase if fresh sources of metal continue to dry up. A consensus seems to have formed around a division of labour within the mining industry that is applicable across all sectors: juniors invest in exploration, and majors offer their financial support once the project’s fundamentals have been established.

Opinions differ as to whether this division is healthy in the long-term. Many projects simply would not reach production stage without investment from a major, and the investment alone can often transform their financing prospects. Oliver Abel-Smith, partner at Fieldfisher, says “often a junior mining company has a single asset, potentially at an early stage, and that's a very different risk profile to a global mining company with multiple projects in multiple jurisdictions at different phases of development.”

These deals can involve equity investments or loans in exchange for offtake. In April, a Letter of Commitment was signed with Pacific Nickel Mines for a $22 million loan towards the Kolosori nickel project in the Solomon Islands. Glencore has secured 100% of the mine’s offtake for six years. Pacific Nickel has confirmed that the loan completes its pre-production financing requirements.

By way of contrast, it was announced in February that BHP had agreed to increase its stake in Kabanga Nickel, a subsidiary of Lifezone Metals, to 17% for $50 million. Lifezone has now progressed to offtake marketing as it approaches first production in 2025.

Yet while major miners offer important sources of finance for new projects, this is not a replacement for exploration. If junior miners are left to carry the burden of discovering deposits, it is inevitable that the metal markets will face shortfalls in supply. The problem is a simple one; juniors do not have enough finance to expand their operations, and the project finance market does not yet see enough value in the mining industry.

It is difficult to avoid the fact that mining is a risk-laden and capital-intensive industry. A consistent flow of finance is required from first discovery to first production, and there is no guarantee that a project will complete that journey. It will be years before an investor sees any form of return, and the lifespan of a mine stretches into decades. To be successful in such an environment, it is crucial that financiers have experience and expertise in the sector. With so many factors at play, the pool of funding is understandably limited.

White & Case’s annual survey of participants in the metals and mining industry highlights the key issues: the macroeconomic background is turbulent, mining costs fall much more slowly than commodity prices, and companies are facing growing pressure to meet ESG standards and share wealth with local communities. It concluded that “the one thing our respondents made clear is the near total lack of certainty and confidence about where the market is headed”.

Certain sectors will struggle more than others; gold and coal miners will not attract ECA funding and must instead compete for support from specialised private equity firms. Africa’s vast mineral wealth has been consistently under-explored because of familiar concerns over country-risk and political volatility. In the absence of real certainty, miners must put together a mixture of funding arrangements that will bridge the gap to first production. They must do so in the knowledge that the available options are limited.

Of all these transaction types, ECA support has garnered the biggest headlines in recent months. The reasoning for their increased involvement is clear: securing a supply of so-called ‘critical minerals’ for their respective industries. Historically, ECA support has essentially revolved around the export of services. Increasingly, recent examples show that ECAs are eager to reach out directly to new mine developments as a means of securing offtake for import. Stringent permit laws have discouraged new mining developments in the US and the EU, so ECAs have looked further afield.

Arafura Resources is currently in the process of arranging financing and offtake agreements for the Nolans project, a neodymium-praseodymium deposit located in Australia’s Northern Territory. It has received provisional untied support from both Euler Hermes and Export Finance Australia alongside offtake contracts with manufacturers including Siemens Gamesa and Hyundai. In 2022, Sweden’s EKN covered an €82 million tranche arranged by Standard Bank and SEK for phase two of the Kamoa-Kakula copper mine in the DRC. EKN’s support came in the form of a more traditional export finance contract without an offtake agreement, but the incentive of expanding the world’s copper supply was no doubt essential to the deal’s success. Project sponsors (Ivanhoe Mines, Zijin Mining, the government of the DRC, and Crystal River Global) had invested around $2 billion in exploration and development already.

Private equity firms often provide the right form of expertise for mines that would otherwise struggle to find support. Firms like Orion Resource Partners specialise in tailoring financing for a specific project through debt, equity, royalties, offtake, or a combination of the above. In February 2022, Sabina Gold & Silver announced closure on roughly $520 million of financing in partnership with Orion and Wheaton Precious Metals Corp. This included a $225 million senior debt facility, a $125 million gold streaming deal and a $95 million private placement of Sabina shares. While this form of support is comprehensive, it is also extremely limited, and most funds will only enter projects at a later stage of development.

Offtake contracts, royalty deals, and stream agreements have become increasingly common as a means of securing value over the lifetime of a mine. In the case of a stream, an investor will be given an agreed percentage of the product itself, while a royalty deal gives a right to a percentage of the mine’s future revenue. However, as with any long-term project, it is difficult to attach value to a product that will not be produced for years to come. The hazards posed by volatile commodity prices or disrupted production become even more serious if a miner has already committed themselves to delivering a certain volume of metal. Shareholder value can be undermined by an undervalued streaming agreement, and royalty deals will include heavy penalty clauses if a mine fails to meet its development milestones.

Some miners have even turned to more exotic funding sources in their quest to reach production. Fieldfisher’s 2021 report on alternative financing for mining pointed to Cornish Lithium’s crowdfunding rounds in 2019. A total of £6.6 million ($8.3 million) was raised from almost 5000 investors, and local stakeholders were given a direct share in the project’s development. This option is clearly not practical for most projects, but it is indicative of the efforts made by miners to secure funding.

A successful project will no doubt be forced to tap more than one of these funding sources, even if it arrives in service of the energy transition. Pent up demand will begin to tell as electrification gathers pace but for those metals that do not fit into a battery, it is tricky to see where financing will come from. A lively M&A market may yet be the prelude to another boom for the industry, but until that moment, the famine will continue.