Today, Washington is still debating the re-authorisation of the ~Export-Import Bank of the United States^ (US Ex-Im), and similar debates are set for Madrid, Canberra and elsewhere. Yet the interesting question is not whether we need the export credit agencies (ECAs), but why do we need them.

There is a broad consensus among export credit insurance professionals not only that US Ex-Im will be reauthorised, but also that it should be. In supporting this consensus, I have to ignore personal interest: as a European and as a practitioner in the private insurance market, I would benefit from the US unilaterally dis-arming their ECA. However, that very argument implies that ECAs are only needed to level the playing field; that the US needs an ECA because rival nations have one; and by implication, multilateral disarmament of the ECAs would be a benefit.

That is not the right way to look at it, however. In the event of multilateral disarmament in our field, if all the ECAs were discontinued, the global trading system would be weakened and prospects for growth and stability around the world damaged. The ECAs are needed partly because in a crisis they provide stability but mainly because, despite the advances of the private market over the past decades, we still need the ECAs’ capacity, even when there is no crisis and the private market is buoyant.

However, that is not the traditional argument advanced for the ECAs. The traditional argument is that the private sector only has appetite for marketable risks, namely shorter term (ST) business, mainly in the developed world; leaving the ECAs operating where the private market fears to tread, and so focusing on medium and longer term (MLT) risks, and in the higher risk emerging market countries. The traditional view is that the private market is risk averse, while the government ECAs have appetite for the riskier business.

This traditional view is increasingly wrong. Today, the ECAs and the private insurers do not operate in separate market segments; there is now substantial overlap between the activities of the ECAs and the private market. The private market, while still lacking enough aggregate capacity, has a strong appetite for MLT business in countries like Brazil, China, Turkey and elsewhere. Furthermore, the private market is more focused on the higher risk emerging markets than the ECAs and has a greater appetite for risks in the poorer rated, higher risk countries in Africa and elsewhere. And far from the ECAs being a market of last resort for the business the private market finds too risky, if anything, the private market writes risks the ECAs reject for risk reasons.

To understand the change that has come about, you must remember that there are two private markets. First, there is the market for conventional multi-buyer short-term trade credit insurance (STTCI), dominated by the monoline private insurers like Euler Hermes, Atradius and Coface. The activities of the STTCI market and those of the ECAs are largely complementary, broadly supporting the traditional view. This STTCI market has a clear run, largely free from government competition, in the EU and the USA; it is pretty well placed to deal with government competition elsewhere around the world, given its global scale; and it remains much less involved in the areas where the ECAs focus their business, namely the more difficult short-term (ST) credit risks in emerging markets and MLT credit risks.

However, alongside the STTCI market sits the second private market, the political risk insurance (PRI) market. Despite the fact that the special risks units of the monoline trade credit insurers participate in the PRI market, the two markets are quite separate. Unlike the STTCI market, the private PRI market provides comprehensive non-payment insurance in exactly the same broad areas as the ECAs: namely the more difficult, lumpy and emerging market focused ST credit risks, and MLT credit risks. This mix of comprehensive non-payment cover is leavened occasionally by some investment insurance-type business. Indeed, the PRI market’s business profile looks very much like that of the traditional ECAs. In reality, therefore, the ECAs’ area of business has become a mixed market of ECAs and private insurers competing for the same business.

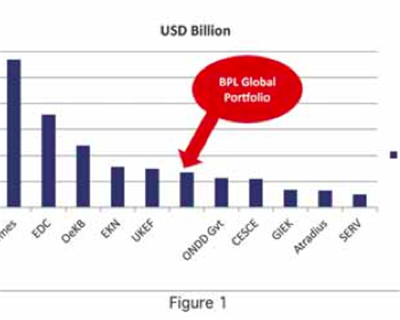

A look at a typical private PRI market portfolio: the PRI market is more exposed in emerging markets than the ECAs

To illustrate how this mixed market has developed, we thought we would show a PRI market portfolio in the manner that the Berne Union members present their activities: broken down into ST, MLT and investment insurance, and analysed in terms of aggregate exposures by country of risk. We can only do this, of course, by looking at ~BPL Global^’s own portfolio. While our portfolio shows only part of the PRI market’s business, it is, according to our insurers, broadly typical of the PRI market as a whole. Our portfolio supports the claims made above.

The BPL Global portfolio of risk as at the beginning of February 2014 amounted to US$27.2 billion of aggregate exposure. The portfolio:

- Consists of all current BPL Global placed policies with private PRI market insurers, regardless of when the risk was originally bound;

- Extends over 20 years, embracing current policies that were bound in 2004 and current policies with expiry dates in 2023;

- Does NOT include exposure in respect of offers or indications of cover;

- Does NOT include exposure in respect of paid, but un-recovered, claims.

We have also only counted policy limits. While over 80% of the portfolio is for single risk cover, the remaining US$5.3 billion is for multi-country policies. These are mainly multi-country investment insurance or political violence policies, where an aggregate first loss policy limit is exposed in many countries. The insurers have to count each exposed country in their country aggregates; we have only recognised the policy aggregate limit. Had we recognised the full country aggregates, our portfolio would be very close to US$40 billion of exposure.

We are of course a broker, not an insurer or an ECA. However, if our portfolio had been written by an ECA, Figure 1 shows that it would be considered as respectable by size, if not large compared to some of the leading ECAs.

We estimate BPL Global has close to a 15% share of the private PRI market. This indicates that the private PRI market has about US$200 billion of aggregate risk, of which about US$100 billion is MLT business. This is a significant amount of MLT business, even in relation to the total Berne Union activity. Given that most exporters can access the whole of the private PRI market, but usually only one ECA, the private PRI market is too big to ignore. If we at BPL Global have an exaggerated view of our market share (we are brokers after all), then the private PRI market is bigger than indicated here in terms of total business on the books.

The Berne Union’s private sector members have for many years only had their activities reported as ST business or Investment Insurance, as they have only been allowed to participate in these committees. Therefore Berne Union statistics on MLT business only reflect the activities of the government ECAs. Even though this may finally be about to change, the practice reflects the official belief that the private insurers are not really engaged in MLT business. In reality, as Figure 2 shows, the main activity of the private PRI market is MLT business. For the avoidance of doubt, the MLT category in our portfolio consists only of policies where the non-cancellable policy period exceeds two years. The Berne Union counts all business with credit periods over 12 months as MLT business.

.png)

Figure 3 shows our overall portfolio, broken down by country of risk. This confirms that the private PRI market’s activities are heavily focused on the developing world. Popular belief has it that the private insurers have more exposure in developed countries while the ECAs are more exposed in emerging markets. This is of course true when you compare the ECAs to the STTCI market. But there are two private markets. The other private market, the PRI market, is more exposed in emerging markets than the ECAs, as illustrated by Table 1. In particular, the ECAs have more exposure than the PRI market in so called ‘marketable risk’ countries, of which more later.

The country profile of our MLT book continues the emerging market theme. Figure 4 shows our top country exposures for MLT business compared to the Berne Union MLT business.This directly compares private sector and public sector MLT activity.

Five countries – Brazil, China, Russia, Turkey and Vietnam – appear on both the Berne Union and the BPL Global list. Yet, while the Berne Union’s top ten is completed by USA, India, Saudi Arabia, Indonesia, and the UAE, ours features Angola, Azerbaijan, Croatia, Ghana and Tanzania. Furthermore, we have three countries from sub-Saharan Africa in our top ten (including Angola, heading our list). In contrast, the Berne Union has none.

Who is more focused on the higher risk emerging markets when it comes to MLT business? It looks like the private PRI market. Indeed, the next five countries in our MLT list are Indonesia, Mozambique, Ukraine, USA and Argentina. With the exception of the USA, the focus remains the more risky countries. The USA, first in the Berne Union’s MLT list, is only 14th on our list of MLT exposure, and the only developed economy in our top 20. Private PRI market insurers not only compete for MLT business, they may also be happy to write business declined by ECAs for risk reasons.

While writing this paper, I performed an internal check on a recently placed policy for a five year conventional buyer credit for an export from the Czech Republic. The case was declined by the Czech ECA, EGAP, for risk reasons. My surprise is not that we had several private insurers competing to write the risk, enough to place it several times over. Rather, my surprise and delight is that we managed to track down the enquiry at all. This is the sort of business we usually never see or get the chance to quote. Much business only comes into the private market if it is first declined by an ECA. The PRI market is viewed by many as a market of last resort. Some ECAs formally have requirements that applicants evidence that the case has been declined by the private market. This is mere window dressing. Private PRI market insurers are risk selectors. Nearly every policy we place with the private insurers has been turned down by a dozen or more other private insurers in the market.

Africa, usually regarded as the continent with the highest risk profile, provides further evidence to support the view that the ECAs are these days more risk averse than the PRI market. Figure 5 shows the proportion of various ECAs’ portfolios represented by African risk and compares it with the 20% of the BPL Global portfolio in Africa.

Over 75% of our African exposure is MLT non-payment risk, and our insurers say our portfolio is reflective of the PRI market as a whole. If this is the case, it certainly appears that the PRI market is writing a higher proportion of its business in Africa than the ECAs are. Indeed, BPL Global alone (part only of the PRI market) has a bigger exposure in African MLT risk – US$3.2 billion – than most ECAs.

Indeed we seem to be witnessing a role reversal. While the BPL Global portfolio of African business continues to grow – with over US$600 million of new placements in sub-Saharan Africa this calendar year – Africa’s share of the US Ex-Im portfolio has steadily declined over the last five years from 6.7% to its 2013 level of 4.9%. Meanwhile the top dozen countries for new authorisations for US Ex-Im in 2013 included the USA (in first place) the UK, Germany, Hong Kong and South Korea. These are not the kind of countries where the PRI market sees much business, even for its comprehensive non-payment cover on private obligors.

Turning to the ST business, the picture of exposure in higher risk emerging markets is much the same. As well as the expected Brazil, China and India, BPL Global’s top ten ST country exposures include the Ivory Coast, Mongolia and Ukraine. But the most interesting inclusion in the top ten is in fact an EU country: Greece.The PRI market has historically not had much reason to write business there. Much has been made by the EU ECAs of them stepping back into writing short-term business in Greece, following the withdrawal of the ‘private market’. But that was the other private market. The PRI market has been doing exactly what the ECAs have been doing: stepping into the breach following the STTCI insurers’ retreat from Greece.

‘The market for non-marketable risk’

At this stage, it is a good time to address ‘marketable risk’: the area of ST business (up to two years credit) in the EU and other developed countries, that the EU based ECAs are forbidden from writing. The term ‘marketable risk’ has some meaning in the context of the STTCI market as those private insurers are protected from government competition in this heartland of their business. But the term ‘marketable risk’ is worse than meaningless in the context of the private PRI market. Only 3% of BPL Global’s portfolio meets the European Commission definition of ‘marketable risk’, and a third of that is our short term business in Greece. As 97% of our business is NOT ‘marketable risk’, it is fair to say that the PRI market can be best understood in Brussels as ‘the market for non-marketable risk’. It is worth remembering this the next time you hear an EU ECA saying ‘we only write nonmarketable risk’ – as while it may be technically true, it is seriously misleading to anyone not intimately acquainted with the niceties of Brussels official terminology.

Nevertheless, it is fair to say that the PRI market is not yet competing with the ECAs across the board. Though there is beginning to be some PRI market capacity available for 15-year risks, not much of the private market portfolio is written for periods of longer than 10 years. So the ECAs still have a largely free rein when it comes to long term credit risks for ships and aircraft, and in comprehensive cover for pure project finance deals. Likewise, the private PRI market only offers pure cover: just over 10% of the Berne Union ECAs’ MLT exposure comes from lending and there is pressure for this to increase further. But increasingly, the traditional view that the activities of the ECAs and the private market do not overlap is not true.

Increasing ECA profits brings increased competition

No one should be surprised by this. Gone are the days when the ECAs lost money or simply broke even. In the last 20 years, the Berne Union ECAs have become powerful cash generators for their owner governments. Arguably they are more profitable than their private market counterparties in either the STTCI or the PRI markets. In its recent re-authorisation process, US Ex-Im has argued that one of the reasons for re-authorisation is that it generates significant revenues for US taxpayers (an argument that might one day come back to haunt it, and not one which is likely to encourage US ExIm to take on more risky business). Elsewhere, EDC paid a C$1.4 billion dividend to its government owner last year while Hermes, commendably transparent about its financial performance, has generated an average positive cash flow of about €1 billion a year for the last 15 odd years.This has helped turn a €13.5 billion cumulative deficit, which peaked in the late 1990s, into a cumulative surplus of some €3 billion by 2012, a total that excludes maybe €7 billion of recovered interest. It is great news that the ECAs have combined supporting their export sectors with generating impressive profits for their government owners. With the ECAs now underwriting largely on a commercial basis, it is not surprising to see the private sector becoming more engaged in the areas traditionally the preserve of the ECAs.

But is the competition from the private market reliable? Did not the private market retreat when the financial crisis hit in 2008? Once again, that was the other private market: it was the STTCI market that withdrew credit limits at the onset of the crisis, the PRI market only writes non-cancellable policies. Furthermore, since the onset of the crisis, the PRI market has doubled its capacity and significantly grown its business. The ECAs have had a good crisis too. But their growth has not been at the expense of the PRI market: the two are increasingly moving in parallel. Certainly, both have seen the last five years as partly a crisis, but mainly as a business opportunity.

Other crises in the past (for example the Asian/CIS crisis of 1997/8) have impacted the PRI market more severely, so there remains a case for saying that we still need the ECAs in case the PRI market retreats in the face of some future, emerging market focused crisis. However, that is not the main argument for the ECAs’ continuing presence in the mixed market. The main reason we need the ECAs is because the market needs their capacity.

Capacity versus appetite

‘Capacity’ tends to be a euphemism for appetite in the ECA world, with risks declined because “we have no capacity for this risk”, when really the case has been declined for risk reasons. However, appetite and capacity are very different matters in the PRI market. Indeed appetite and capacity tend to be inversely-related: insurers tend to have lots of capacity in the countries where they have little appetite for writing risks and vice versa.

The reason is that, unlike some ECAs, all private PRI insurers write within strict buyer/borrower and country aggregate limits. These limits are set by the insurers based on the amount of premium they expect to write in the class of business, their own ability to retain risk on their own balance sheet, and the limits of their reinsurance treaties. Normally PRI market reinsurance treaties allow the insurers to write business globally (except for sanctioned countries), and with maybe sub-limits for different country categories. In other words they leave the ceding insurer to build their portfolio as they wish within broad obligor and country aggregate limits. When it comes to obligors, an insurer’s capacity for a ‘B’ credit is much the same as their capacity for an ‘AA’ credit. Either might default. The fact that a PRI insurer might use less of their capacity line size on a ‘B’ credit and more on an ‘AA’ credit is a function of appetite, not capacity.

So when a PRI insurer turns down a risk in Sudan, it is likely to be for lack of appetite – either for the particular risk on offer, or because they do not want to build a large aggregateinsuchariskycountry.Asaresult, the PRI market has a lot of unused capacity in Sudan. In contrast, when a PRI insurer turns down a medium term risk on for example Petrobras in Brazil, it is likely to be for lack of capacity, either on Petrobras themselves or lack of Brazilian country aggregate. They may have plenty of appetite for Petrobras risk, with much exposure already on the books, but as a result they may have no remaining capacity.

Though it is difficult to be precise about its size, the aggregate capacity of the PRI market is not large. If the private PRI market has say US$5 billion of aggregate exposure for non-payment risk in a country, it will be near or at the market’s aggregate exposure limit for most countries.When the market is full, it simply turns business away. The market’s country aggregate is much the same for each country within a country category, though some adjustments may be made for maximum probable loss scenarios depending on the portfolio mix.

US$5 billion is not a large number when you consider the size of the demand for export credit insurance for the big markets like Brazil, China, India, Russia and so on. The Berne Union ECA members alone have over US$600 billion of exposure to MLT risk around the globe. With the ECAs typically lumpy exposures, we can assume this exposure is not well spread. Indeed, we know that the Berne Union ECAs have about US$30 billion of exposure in both Russia and the USA, and plus or minus US$20 billion of exposure in each of their other top ten countries like India, Turkey, Brazil, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, China, Indonesia and Mexico. Were the ECAs not there, there is no way this exposure could be absorbed by the private PRI market.You need to make no other argument for the ECAs than this one about capacity.

Nor will the private PRI market have that type of capacity any time soon. Collectively of course the private insurance industry has the capital base to run very high exposures. Catastrophe models are geared to the industry paying out +/US$100 billion on single event risks that will happen sooner or later: the Tokyo or California earthquakes and the East Coast windstorm being the most obvious examples. Therefore the industry could in theory run the same level of aggregate exposure to Brazil or China aggregate risk.

However, that is a long way away. It has taken over three decades for private market capacity to build to its current level, and that is about two to three times the level of the PRI market’s annual premium income. We anticipate that the market’s premium income and country aggregate capacity will continue to grow. But we are going to need the ECAs’ capacity for a very long time.

There are some signs that the ECAs are beginningtoseethatitiscapacity,notrisk appetite, that underpins their role. Hermes in Germany, like other ECAS, has traditionally described their role as providing cover in the countries where cover from the private market is not available. In their 2013 Annual Report, the argument subtly changes, as they state their role is to provide cover where the private market does not have ‘sufficient’ capacity.

This is a small word, but it makes a world of difference. It concedes that there is indeed a market for the ‘non-marketable’ risk that Hermes writes, albeit a market which has capacity constraints on certain popular buyers and countries. However, it is also a market that may have a greater appetite for certain risks than some ECAs. This acknowledgment carries with it a profound message both for the ECAs themselves and their clients.

A mixed market of choice

The ECAs’ clients need to recognise, if they have not done so already, that they have a choice. ECAs and the private insurers are often interested in writing the same business. The private market may write business that their ECAs have rejected. Where the ECAs do offer cover, the private market may offer a better product at a cheaper price. Exporters and their bank financiers need a relationship with both their ECAs and the private market.

The market for MLT business is a mixed market of public and private insurers and clients need to learn to shop around. Clients should also be aware that despite the private market’s lack of national interest eligibility criteria, it does not guarantee a level playing field. The PRI market’s scarce capacity is allocated partly on a relationship basis: exporters and banks with a good knowledge of and relationship with the private market can find themselves with a competitive advantage.

For the ECAs, a tacit acknowledgement that there is indeed a market for the “non-marketable” risk they write is recognition that they are not simply writing risks for which the market has no appetite. Rather, they are increasingly providing additional capacity for risks where the market has strong appetite but may have limited capacity.The ECAs in other words are part of the mixed market.

The issue of competition

However, when the ECAs operate in a market place, at the same level as their private market competitors (as that is what they are), they are entering an alien environment. The ECAs need to adapt to the workings of the market.

The ECAs are used to operating in a world where the OECD Consensus limits competition between insurers; in contrast the PRI market operates in a world where competition is entrenched and enforced by strict laws. In the ECA world, when risks are shared, this comes about through cooperation with different insurers discussing with each other the terms, conditions and pricing of cover; in contrast, in the PRI market, risk sharing takes place in accordance with the competitive dynamics of the subscription market. There is no ‘cooperation’ between the insurers, and they do not talk to each other while the client is shopping for cover in the market; each insurer only talks to the client about the terms and pricing of their portion of the risk.They have to compete for the leadership or participation in the placement.

There is of course a danger that the mixed market sees ECAs competing unfairly with the private market. However, in my view, that danger is not as great as the danger that the ECAs restrict choice available to the client. There are two ways the ECAs can restrict the client’s choice. The first is by withdrawing from the market and not offering cover for ‘non-marketable’ risk when the private market is available.We at BPL Global think this would be wrong. We do not want the mixed market to be run for the benefit of the private insurers: we want it to be run for the benefit of the market’s clients. You do not benefit the clients by curtailing the activities of the ECAs and restricting choice. The second way the ECAs may restrict the client’s choice is if they fail to understand the rules of the market and fail to follow subscription market practise, in which the client, not the insurers, organise risk sharing. If the ECAs try to organise the market themselves they will disrupt the proper operation of the market place and risk damaging the client’s interest.

This is a different subject however, and a consequence of the theme of this article.The conclusion of this article is only that the ground is shifting: the need for the ECAs is not because they have a greater risk appetite than the private market but rather because they provide capacity into a market that has a significant appetite for risk, but limited capacity.

.png)